U.S.-Russia de-escalation over Ukraine is still possible – but time is running out

Conflict results from failure of imagination, not lack of options

February 7th, 2022 | SIT Graduate Institute

By Dr. Bruce W. Dayton

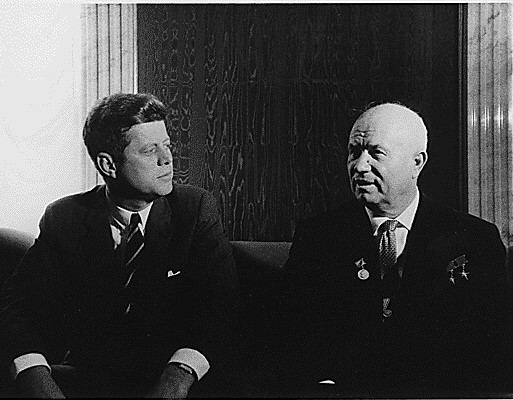

National Archives via pingnews

International crises such as that occurring between the United States, its NATO partners, Russia, and Ukraine often tragically fall into what is known as a “spiral of escalation.” Each side stakes out an extreme initial position and holds to it, believing that a hard line is the only way to maximize their gains.

Making concessions is viewed as a weakness. The conflict is seen as zero-sum; what one side gains the other loses. Threats and coercion are used to convince the other side that rejecting agreement will be more costly than accepting the terms being offered. Acting on the premise that the other side is guided only by a drive for power and can be influenced only by coercion tends to confirm these results.

Conflicts under such conditions often become unstable and destructive, especially when both sides adopt increasingly severe tactics at the same time. With neither side willing to make concessions, creeping intensification or protracted stalemate results. Worse, a miscalculation can trigger a rapid and violent escalation resulting in war and untold suffering.

Such spirals can be reversed, but only when each adversary comes to believe three things: first, that they are incapable of prevailing over their opponent; second, that a better option is available; and third, that working together to contain the conflict is more likely to achieve desired ends than the unilateral imposition of will. Ukraine and some members of NATO appear to have reached that point, Russia and the United States have not.

Beneath the mutually exclusive demands being made by Russia and the United States are a set of shared interests, among them regional security, prosperity, and recognition.

Several steps remain possible to help bring about a ripe moment between the U.S. and Russia.

First, negotiators from both sides could eschew zero-sum bargaining in favor of integrative bargaining. After all, beneath the mutually exclusive demands being made by Russia and the United States are a set of shared interests, among them regional security, prosperity, and recognition. Whereas zero-sum positions are non-negotiable, shared interests are negotiable. Such a step is unlikely to occur without assistance from a third-party mediator acceptable to both sides. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has made such an offer. A more likely possibility is French President Emmanuel Macron, who is visiting Moscow and Kiev this week.

Second, negotiation tends to be more successful if the parties first address the issues that are easiest to resolve, leaving more contentious matters to a future date. Focusing on the most solvable aspects of a problem builds trust between adversaries and gives the parties time to cool off, even as they search for creative solutions to more intractable issues. One example of this is the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed by several western powers and Iran in 2015. It was successful because it narrowly focused on sanctions relief for inspections rather than the more fraught and complex issues separating the parties to the agreement. That deal would likely have led to more significant progress on U.S.-Iranian relations had it not been scuttled by President Trump in 2018.

Third, Russia and the United States need to make sure to stay open to face-saving pathways to de-escalation. Currently, each side is dug into an unyielding position with leaders making public pronouncements of victory at all costs. Such pronouncements are problematic when it comes to finding off-ramps to a conflict. Compromising or getting less than promised may be perceived by the public as a defeat.

Second-track diplomatic initiatives had a long and successful track record during the cold war, allowing influential individuals, ex-officials, and other informal actors on both sides to exchange ideas and unofficially discuss areas of agreement.

Face-saving addresses this problem by creating innovative compromises that allow each side to de-escalate while declaring victory. One famous example of this was the deal agreed to by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and U.S. President John F. Kennedy that ended the Cuban missile crisis. In that case, Khrushchev agreed to dismantle Soviet nuclear sites in Cuba in exchange for Kennedy removing U.S. missiles from Turkey and publicly expressing regret over a U2 spy plane incursion into Soviet territory.

Fourth, a second-track diplomatic channel can be opened outside of the public spotlight. Such initiatives had a long and successful track record during the cold war, allowing influential individuals, ex-officials, and other informal actors on both sides to exchange ideas and unofficially discuss areas of agreement. Breakthroughs in the track-two realm can then be fed into official track-one channels, illustrating where common ground agreements are possible.

Finally, citizens can play a role by strengthening constituencies for de-escalation. Indeed, extensive economic interdependence, as well as educational and cultural programming, already exist between the United States and Russia. Such constituencies can publicly pronounce their concerns, remind policymakers of what would be lost with an overt conflict, and mobilize supporters to be more active and vocal.

None of these steps is easy, particularly given that we are in a moment of crisis—one in which time is short, the threat is high, and there are significant uncertainties. In the end, however, destructive conflict is the result of a failure of imagination, not a lack of alternatives.

Dr. Bruce Dayton is chair of SIT's master's degree in Diplomacy and International Relations. He is co-editor of Waging Conflicts Constructively: Principles, Cases and Practice.