‘Africa is going to give the world a sense of humanity’

A conversation with Cape Town Academic Director Stewart Chirova

October 26th, 2023 | Africa, SIT Graduate Institute, SIT Study Abroad

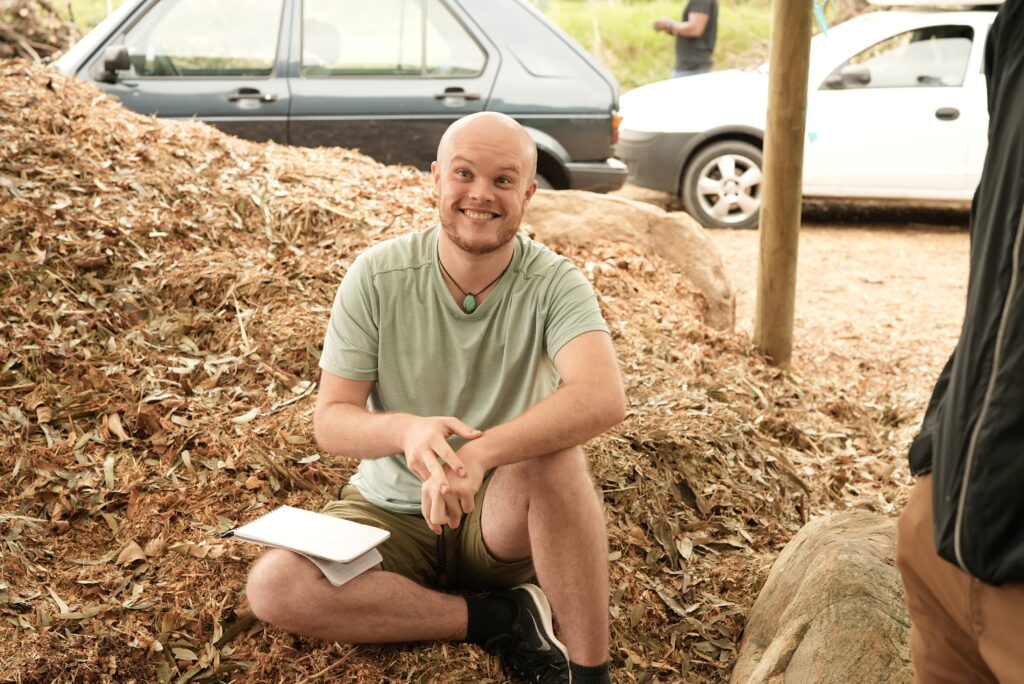

STEWART CHIROVA is academic director at the School for International Training learning center in Cape Town, South Africa, one of SIT’s busiest learning centers in the world. Chirova leads the semester-long South Africa: Multiculturalism and Human Rights program and the summer Social Justice and Activism internship. His center this year also hosted students in two SIT Global Master’s programs: Diplomacy and International Relations, and Sustainable Development Practice, as well as various custom programs designed with U.S. colleges and universities.

Chirova has worked with SIT for nearly 20 years. We talked with him about experiential learning, reciprocity, racism, and the many students who come through his programs. Following are excerpts from that wide-ranging conversation.

You originally started with SIT in Botswana in 2002, then in 2010 you came to Cape Town, so you've been working with U.S. students for many years. What draws you to this work?

The work that we do at SIT is life-changing. What draws me to this work is that after spending 15 weeks with the students on a daily basis, you see the growth, you see the change, and you see the kinds of global citizens that are developing. Being part of that makes the job very satisfying.

I imagine that you would see growth and change in any student population. Is there something specific about the growth you help to guide in U.S. students that motivates you?

A lot of American students are very good and knowledgeable about America, but their worldview sometimes is limited. Given the positionality of America and American exceptionalism in the world, it is even more important to give them - a broader worldview perspective—given the positions they may hold in future. One of the things that I always say to my students is that I'm not so worried about their aptitude, because SIT has a rigorous admissions procedure, but we want to nurture and develop their emotional intelligence.

I'm motivated by Nelson Mandela. One of the things that he said about Africa was that all the industrialized countries may have given the world technology, but Africa is going to give the world a sense of humanity. That's why we do what we do here.

That goes well beyond academic teacher or mentor. What does the role of an academic director encompass?

We are both mentors and coaches to our students. I'm a mentor because I try to develop them in the things that I know and the things that they are trying to know, but I'm also their coach because I'm trying to unleash the potential that they may be sitting with but don't realize they have. So, I see my role as balancing mentorship and coaching in order to bring the best out of my students.

Reciprocity is an SIT value. What does that mean to you? How is a student reciprocal when they are here or when they leave?

Sometimes people think about reciprocity as something that must be tangible, like they built this, or they gave that. That becomes like aid, right? There should be a difference between aid and reciprocity. Reciprocity starts with respect between people. When the students arrive, we remind them that their experience here could either be extractive or reciprocal. When they write [on a resume or job application] that they've studied abroad, for example, that sentence alone is going to help them a lot. Having a letter of recommendation that says you've studied abroad can do wonders in one's life. But how do they actually give back to the communities that may have changed their lives?

We don’t want that relationship to be extractive. We want it to be reciprocal, so that it's not only the student who is benefiting from this experience but also the communities they're working with who are also benefiting from the experience. Study abroad must be a cultural exchange, if that exchange happens and the program design is intentional, then to me reciprocity has been achieved.

Can you talk about your approach to the SIT experiential learning pedagogy?

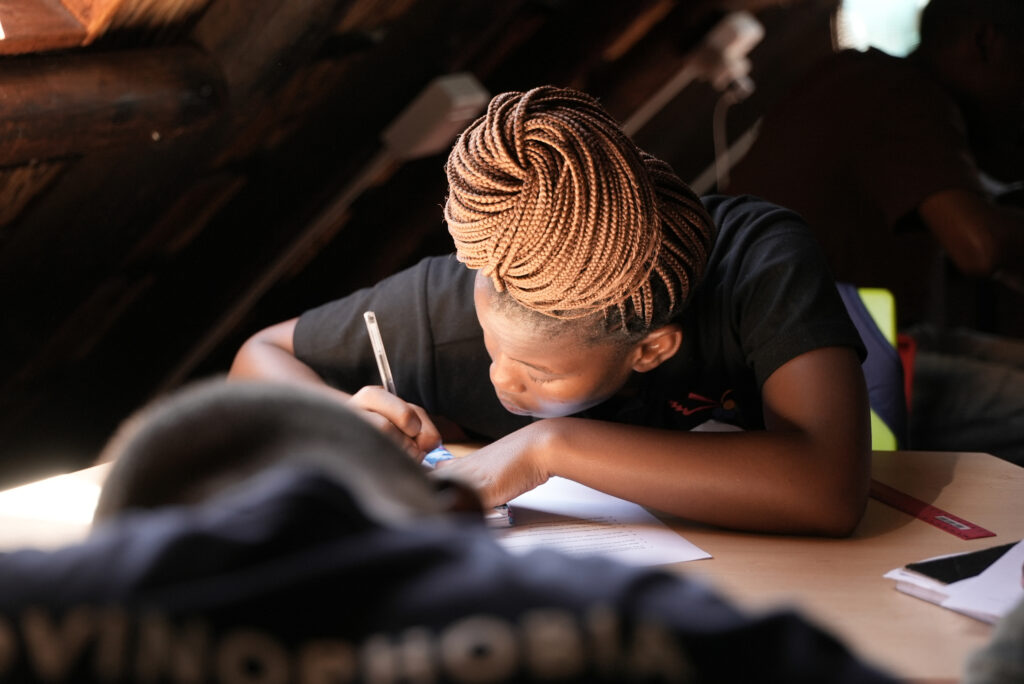

Most of our learning in college is that the professor comes in and they tell you what to do and then you have to give them back what they told you at some point. Experiential learning invites you to be an active participant in the experience. You tend to remember what you did and especially if you reflect on it, you may actually come up with more questions than answers.

The way I try to explain SIT’s model of experiential learning to our students is that of course it's a cycle, and like any cycle, the entry point can be anywhere. But we always start with the experience: There must be an experience at the top and this must be followed by a reflection of the experience. There must be abstract conceptualization at the bottom, and then you have to test your assumption, or the lessons learned, by applying- the new knowledge that you have learned to new situations.

One of the things that we talk to students about is that they must have time to reflect on the experience itself, because that’s when you start asking deeper questions about what you have gone through.

Through that reflective experience they start seeing the similarities and the differences between the U.S. and South Africa

American students like to use the word “weird.” I invite my students to try not to use the, word “weird” when they're here, but to say “different.” By accepting “difference,” immediately you are going to ask the question, “What is different about this?” And that's when the reflection starts. The more you ask those kinds of questions, the deeper your understanding of the phenomena or the event is going to be.

I always try to explain to my students that there's a difference between being educated and being learned. An educated person knows how to answer questions about the knowledge that they have in their heads. A learned person can ask deeper questions about the same knowledge to find out more.

So, the process begins with experience, and obviously the experience begins when a student comes off the plane and comes to their community and their homestay. Can you describe the arc of experiences that you hope to provide over the course of your program?

Because our programs are steeped in issues of oppression and race and racism, one of the things that we try to help our students understand is that these issues are not unique to South Afric. Our students may have come here to learn about South Africa, but they're going back home having also learned more about the U.S. and how systems of oppression work. I warn students that when you reflect on something, you are more likely to see yourself in it. Through that reflective experience they start seeing the similarities and the differences between the U.S. and South Africa.

But more importantly, we want to inspire them to think about what then. Now that they know this information, now that they know that this is how the world works, what are they going to do about it? Sometimes people say that it's hard enough not knowing what to do, but it's even harder not doing something once you know what to do.

Many of today’s students have had to confront race very directly since 2020 with the attention given to the murder of George Floyd and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement. How are you working with your students around these issues?

One of the biggest things that we have to deal with in this program, almost every semester, is group dynamic issues that are centered on race. Of course, Black students have a lived experience of what it is to be black in the U.S. When they come here, one of the things that confronts them is the grand narrative about South Africa that is out there. Most people think that South Africa has solved its past issues when it comes to race and racism. When they come here, the students find it very difficult. Black students often find out how they are more American than African, when in fact they may have come here hoping that they're coming home, but they quickly find that home is not actually what they perceived it to be.

White students sometimes don't know how to ask questions; they don't know how to talk about race in the presence of a person who has that lived experience. I never call my class a safe space because there's no such thing as safe space. But there is brave space, where you can actually sit and talk about deep issues that are affecting communities.

I never call my class a safe space because there's no such thing as safe space. But there is brave space, where you can actually sit and talk about deep issues that are affecting communities.

When you start talking about race, one of the things that's easier for us here in South Africa is there's no political correctness. As soon as you arrive at the airport, you're going to be categorized in some sort of racial category. Why? Because that's how people relate to each other: I can't know how to deal with you unless I box you into a racial category. So, the way you're going to treat me, the way you're going to talk to me, is based on that racial category. In order for me to know how to deal with you, I'm going to box you and then we'll find each other along the way.

In fact, here, people are so open about this that if they're not sure what race you are, they'll ask you. So, we start off with that with our students: What does it mean to be boxed in a racial category in the South African context? What does it mean to be boxed in a racial category in the U.S. context? Once you start talking about race like that, it becomes easier to talk about white privilege without creating a hostile environment in the class.

You also have SIT Global Master’s students who come to South Africa on one of their semesters. Do you think an experience here as part of a master's program might help a student to move into their desired career field?

I think an experience for master's students anywhere outside the U.S. is going to be enriching. What we see when students come here is this new way of learning. One of the unique things about SIT is that it’s changing how master’s programs and graduate programs are run. Graduate programs have always followed this very traditional way of learning that has remained unchanged for many, many years.

SIT is well-placed to change that because we have learning centers all over the world. Imagine the opportunities that exist in these countries, the networks that exist, and the exposure that the students are going to get. You can be at an American university doing a master's program but all the faculty there might be Americans. On our Diplomacy and International Relations program, for example, students start in Washington, DC, where they may get an American perspective from American faculty. Then they go to Switzerland, where they're going to be taught by different people, who also teach differently.

One of the unique things about SIT is that it’s changing how master’s programs and graduate programs are run.

Then when they come here, they are exposed to yet another way of learning. At the grad level, this prepares students for the real world because when you are out there working, you're not going to be working with just people from the U.S., especially if you're in the field of international relations. You're going to have to learn how to talk to different people. So just by moving around in these different countries, in true SIT sense, we are exposing students to working with people internationally.