Looking for climate connections (and berries) through traditional Indigenous knowledge

November 21st, 2023 | SIT Graduate Institute

When trying to protect lands from the onslaught of climate change, start by asking the people who know those places and their wild inhabitants the best.

October 5, 2023

Dominique Nault is a member of the Chippewa Cree Tribe in Rocky Boy, Montana. She is toward an MA in Sustainable Development Practice at SIT. This story was originally published on the website of the Natural Resources Defense Council. It is reprinted here with permission.

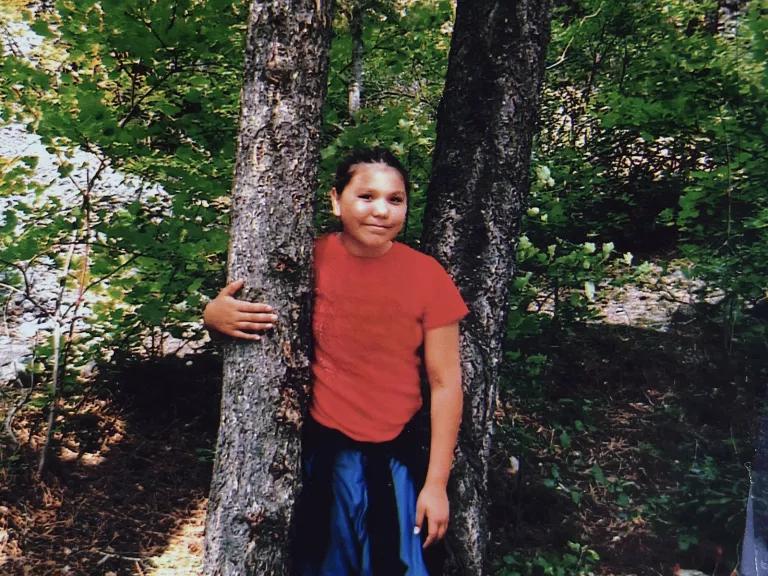

I sit on the passenger side of my father’s black, beat-up pickup truck, my eyes slowly getting heavier with each bump on the rough back roads. I am only 10 years old, but the Bear Paw Mountains, located on the Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation in north-central Montana, are no stranger to me. They are my homeland.

Long ago, a prophecy warned the Ojibwe about the arrival and western expansion of Europeans, urging the tribe to go to the land of the big mountains. This eventually led my ancestors’ band to Montana. The Cree, or Nehiyaw as we call ourselves, have come to these sacred mountains for hundreds of years to give their offerings and to pray. For most Indigenous groups in North America, unique environmental landmarks should be protected and kept clean like any place of worship.

Our truck squeaks to a stop, and I take in my surroundings. Giant trees make the air smell like damp wood and their canopy of leaves allows only streaks of sunlight to pass through the dense underbrush. Where we’re headed isn’t accessible to anything with wheels, so we’ll have to walk from here. I grab my empty gallon ice cream bucket and follow my dad down a path hidden by overgrowth. Several of the bushes and plants we walk among can be used as medicine, my grandma had taught me. “Stop when you smell the peppermint. If you reach a meadow, you’ve gone too far,” were the only directions we got from her that day. She had sent us to the mountains for bonding time and, of course, for berries.

Soon, the scent of peppermint fills the air, and I realize that we are near the spring. “Astum!” shouts my dad in Cree, commanding me to bring our canister and fill it with the fresh cold water that has emerged from the mountain’s surface. “This water is as good as that fancy stuff they try to sell back to us after ruining our water supply,” he says.

Now, we must climb the side of the mountain, up to where we will find the best Juneberries, and if we’re lucky, raspberries, blueberries, and others. Most families have their secret spot for berry picking, but I am biased and know that ours is the best. I mean, where else could you find so many different varieties in one area? When we finally arrive, I begin filling my bucket.

But every year, there are fewer berries. My grandpa says that something is really wrong, but I am too young to understand what is yet to come.

Fighting climate change with tradition

More than a decade later, as I work toward my master’s degree in sustainable development, I take note of the impacts of a warming world on Indigenous lands around the globe, altering landscapes along with water and food sources. In Montana, it has made its mark in numerous ways: melting glaciers, hotter springs and summers, more wildfires, less snowpack, less water. On my reservation, drying wetlands have caused a decline in sweetgrass, a sacred prayer grass that is also used as an antiseptic. My culture is based on the health of the environment, so when a species disappears, so does a part of something bigger—a connection, an ecosystem, a people’s way of life.

While Indigenous People worldwide make up less than 5 percent of the human population, we protect 80 percent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity.

Fossil fuels and habitat degradation contribute to these losses, and these are things we often can never get back. As I look back on that little girl walking through the mountains, I mourn. What will become of us when the climate crisis sickens the forests, rivers, oceans, and soils that we all rely on? What will happen to us when the earth no longer gifts us with sustenance?

Tomatoes. Cacao. Squash. Corn. Beans. Potatoes. Peanuts. An estimated 60 percent of the foods eaten around the globe today originated in the dietary cultures of Indigenous Peoples in the Americas. They also contributed to more than 50 present-day medications, including aspirin, the most commonly used drug in the world. Traditional hunting, gathering, and agricultural practices respect the land and its ecosystems and help cultivate crop diversity. In fact, while Indigenous People worldwide make up less than 5 percent of the human population, we protect 80 percent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity.

We certainly deserve a seat at the table in climate, conservation, and other environmental policy decisions, and Indigenous consultation should be a top priority at each step in these discussions taking place around the world. Not only are Indigenous communities often the most at risk from the effects of climate change but we are also very adept at adapting to them. Uniquely tied to our lands, our knowledge is invaluable. We know where to look for the berries. We notice when there are fewer of them. We know how to take care of our special spots.

Dominique Nault is a member of the Chippewa Cree Tribe located in Rocky Boy, Montana, working toward a M.A. in sustainable development practices. She is currently researching how to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), utilizing her language to develop climate adaptation strategies. Nault has also worked on numerous projects, including developing cities' climate change toolkits, incorporating TEK, food desert solutions, and water and air quality programs. She holds a BA degree in environmental studies, with a double minor in climate change studies and journalism, from the University of Montana.