How teachers are learners, and other parting thoughts from Dr. Leslie Turpin

July 20th, 2023 | SIT Graduate Institute

By Kate Casa

After more than 30 years at School for International Training, Dr. Leslie Turpin retires this summer from her position as chair of SIT’s Master's in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, or MAT. Turpin brings a broad range of interests to her teaching, and a uniquely inclusive approach to language as an entry point for all learning.

“I believe that the way to solve the world's problems is to learn better,” says Turpin. “We need to figure out how to learn differently. For the MAT program, language is the portal to that bigger question: What does it mean to learn? How do we evolve as human beings through the process of learning?”

The daughter of a German immigrant, Turpin’s early cross-cultural experiences stirred a lifelong quest to understand and make meaning out of language, culture, and place—her own, her family’s, and the students and teachers with whom she interacts.

Language teaching for me was always a vehicle for something more.

She studied anthropology as an undergraduate, then volunteered with VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) teaching English in an immigrant community in New Orleans, which sparked an early interest in working with refugees. It so happened that Turpin’s VISTA supervisor was an SIT alum who had worked in refugee camps, and she followed his recommendation to “go to this school up in Vermont.”

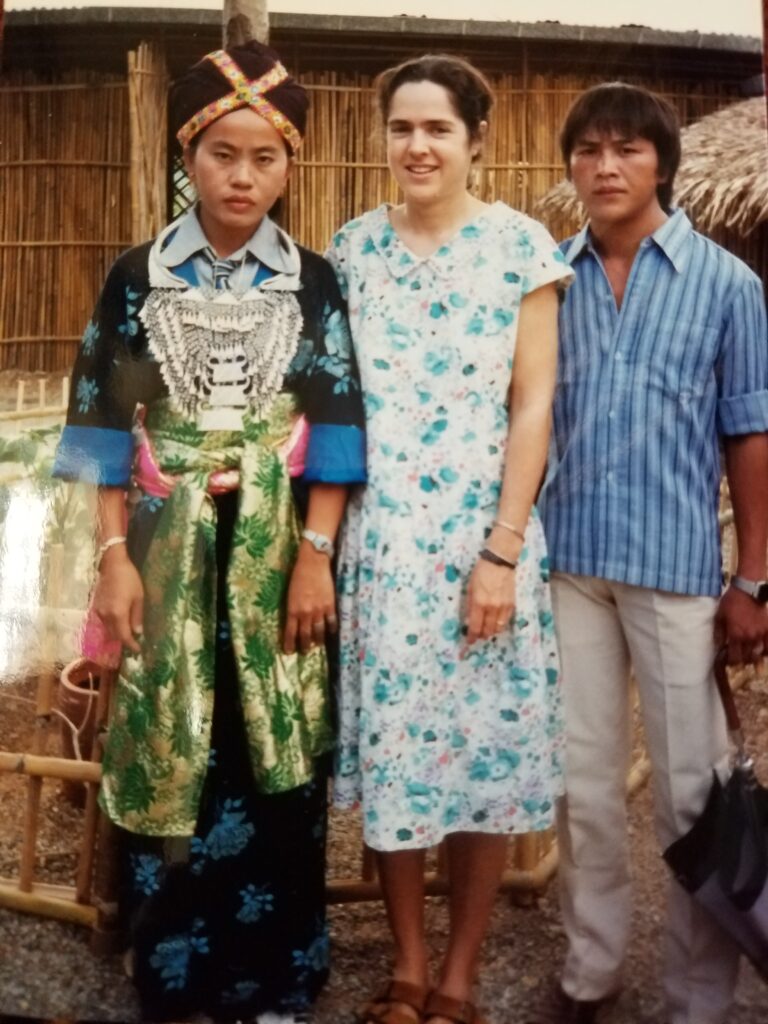

After completing her MA at SIT, Turpin and eight or nine of her fellow alumni began working in refugee camps in Thailand. “Language teaching for me was always a vehicle for something more,” she said. “When I went to the refugee camps, I did teacher training; then I came back and just kind of fell in love with teaching and learning and felt like that was a great way for me to be connected to people in a way that I had something to offer and where I could learn. I learned so much.”

Learning is at the heart of Turpin’s approach to her work and her life. Among the Lao migrants she met in southern Vermont was a musician whose music and lyrics caused her to consider “his relationship to place.” That interest drew her to the Vermont Folklife Center—which she calls her “spiritual core”—an organization that documents and shares Vermont communities’ everyday expressions of tradition, innovation, and culture.

Although she is also wrapping up her tenure as board chair of the center, Turpin intends to keep her fingers on Vermont’s cultural pulse. She also plans to continue working with refugees in southern Vermont, where she and other SIT faculty and emeriti volunteered to develop and deliver language and cultural orientation programs for Afghan refugees who were evacuated in 2021 after the Taliban re-took control of that country.

As she prepares for “retirement,” we talked with Turpin about her time at SIT. These are excerpts from that conversation.

You have a very wide range of interests—in the arts and in memory studies for example. What drew you professionally into the field of English language learning?

I had gone to a refugee camp in Thailand with a number of grads from my MAT program. I think there were probably eight or nine of us all working together; the camp programs had really been developed by MAT faculty. So, we felt like we were stepping out of school and into working in the camp, which was so connected philosophically.

But I kept coming back to my own family's history, having come here as refugees. So, when I went back to school for my doctorate my advisor and I came upon the question of how children whose parents are refugees experience their parents' memories of place.

Place was such an important part of people’s transition—what they missed and what they lost and what they were trying to rebuild. I was interested in ecological identity and how people are defined by the places they live and the geographical features. So, I started doing my doctoral work with the Lao community in Brattleboro, where I had been tutoring one of the Lao families when I was a student in 1982.

My doctoral work started with a focus on children and how they were experiencing their parents' memories. But then I became connected to the parents and what their experiences were in trying to convey their memories to their children. One of the people in my study had been a famous musician in Thailand and Laos and I got really interested in music and in his life as a musician and the lyrics of his songs and how much those conveyed his relationship to place.

Then I found the Vermont Folklife Center, which became sort of my spiritual core. The center supports people sharing and documenting their everyday culture. At the same time, I started working at Sandglass Theater, which is devoted to intercultural communication and dialogue and memory. So, I was pulled into that as the managing director of that theater.

And that pulled me back into my own family and an exploration of my own relationship with my parents, and particularly my mother's place and her family. All those things, for me, are not necessarily all about language teaching, although my doctoral work was also around language teaching.

It sounds like English drew you into all these other fields—that language teaching became a portal for you.

Exactly. Language and culture are so core to who we are and how we express ourselves, and when we don't have the language in another culture, or if, as a child, you don't have your family's home language, you don't have access to your own identity and your past. So, language learning and language teaching within the context of understanding people's identities became interesting to me.

Language teaching is so deeply about who we are fundamentally. It’s why the MAT program has been important at SIT. It's both language and culture. I believe that the way to solve the world's problems is to learn better. We need to figure out how to learn differently. For the MAT program, language is the portal to that bigger question: What does it mean to learn? How do we evolve as human beings through the process of learning?

For the MAT program, language is the portal to that bigger question: What does it mean to learn?

In The Silent Way [an approach to language teaching devised by Caleb Gattegno], which influenced my thinking a lot, is the idea that we each have the right to evolve, and that's the right to learn. We also have the responsibility to learn better because that's how the whole human boat rises. When I look at all the issues that our other [SIT] programs deal with, I feel like learning is central to them.

Our program is not so much about teaching, it's about learning. Teaching is the response to learning. Gattegno used to say, “Learning tells you how to teach.” The only way to know how to teach is to watch learning. What it means to be learning your students is to be watching and observing and then responding in a way that is going to help the learner make the next leap forward in their learning without robbing them of that opportunity of making the jump themselves.

Our program is not so much about teaching, it's about learning. Teaching is the response to learning.

Often, teaching is, “I'll give you something and you absorb it.” We've always been the opposite of that, which is, “I need to see where you are, and then I need to see what the next leap is that you need to make. And then I need to figure out how to help you make that leap without making the leap for you.” It sounds so simple, but I feel like it requires so much discipline on the part of a teacher.

How do you think you most contributed to this program and shaped it over the 30 plus years that you've been here?

It was never about what an individual brought. It was always about what we, as a group, created together. So, it's really hard for me to say, “I brought this” or “I brought that,” because what I brought was participation in a process of co-creation and wholehearted participation, just as everybody else did.

I spent a lot of time working on student papers, writing responses to them, not so much correcting them. I read student work thoughtfully and tried to find a way to connect to them and respond to their work with deep listening. I think the same is true when I supervise teachers. I'm never going there to correct their teaching. I have to leave my own beliefs about teaching at the door and just try and be there in a supportive role to say, “What are you trying to do here? What do you want to work on? What can I do to help you? What can I help you see?” We want people to learn for their own sake and develop that ability to learn on their own. That's the hardest thing to do.

The hard part of learning is to have to get up every morning and figure out what you're going to do, how you're going to do it, make it happen, and then figure out what you need to do next. In the MAT program, that's the work of the student.

You know, I homeschooled my son in high school, and he had to get up every morning and figure out what he was going to do. He did amazing things. But we agreed he should go to the local high school for physics because he wasn't going to be able to tackle that alone. So, he went off to school and came back the first day. I said, “How was that?” And he said, “It was so easy. They tell you what to do. They tell you how to do it, they tell you when to do it, and then they tell you how you did.”

I realized that is easy learning. The hard part of learning is to have to get up every morning and figure out what you're going to do, how you're going to do it, make it happen, and then figure out what you need to do next. In the MAT program, that's the work of the student, and that's what we want them to try and learn to do with their students.

It's really a respectful, regenerative process of teaching and learning. Is there any other program like it?

I don't think so. That's what makes us unique. In many ways, this program was ahead of its time. There are a lot of ways that education has changed, and the program has changed and needs to continue to change. We introduced plurilingual pedagogy. We’ve examined structural oppression—there’s no end to that; you just go deeper and deeper. Those are good things to be moving forward: the movement away from monolingual language instruction and the place of privilege that monolingual English language teachers have held for so long in the field. Breaking that open and recentering where the power should be and how much the field can learn from people who've learned multiple languages.

And one thing we've always believed in is the joy of learning. We used to have this saying based off the book The Unbearable Lightness of Being: "an incredible sense of purpose with an unbearable lightness of being.”

Do you have any idea how many souls you have inspired out there in the world? How many students have gone through your program?

I think it's almost 3,000. I really don't know. It's a lot. I take so much comfort thinking how MAT lives within all these people—if they are working with what there was to learn here, if they're taking it on and expanding and improving, if they’ve made their learning their own. Then there’s all the students that they have taught and who have been influenced and impacted by them. I just think it's extraordinary the impact that this little program has had over its lifetime.

What are you taking with you as you go forward?

I've been part of an inquiry group of former MAT faculty. We've been meeting pretty much since 1990. It was part of our mentoring into the MAT faculty. We had a reflective practice process that we started together, and it became so popular that the other faculty wanted to join. The kernel of that idea has lived on. There are six of us who are still meeting and we're working now to figure out how we take what we've learned as a group and bring that to other people.

I just think it's extraordinary the impact that this little program has had over its lifetime.

There's one alumni who's asked me to work on a project with her, which I'm really excited about. And I'm working a lot right now on my own family memory and that question of my dissertation: how children experience their parents’ memories of place. I've finally brought that home to myself and I'm really excited about that exploration as a self-ethnography.

And it's an exciting time in Vermont with so many new refugees here.

Yes, and I definitely want to be involved with the refugees in Brattleboro, even as a substitute teacher in the language classes or a conversation partner. There's a group of former faculty and emeriti meeting to talk about our next step as a group and how we can be of service. And then, I've got grandkids. I've got a daughter in Denmark. I just got German citizenship. I want to spend time in Germany. Getting citizenship, I had to do a lot of exploration of my family and of their refugee experience. So that’s opened this whole door.

Those are some exciting new chapters. Do you have any parting words?

Just a sense of gratitude for my colleagues over the many years; for all the teachers who have worked in the program and helped to shape it; and to all the students who are out there living that work. I think it's really challenging to be a teacher right now and I am in so much awe of them doing that work.

One of the people who's really influenced me a lot is Shakti Gattegno, Caleb Gattegno's wife. I'm still in touch with her. She's 98 and has been a remarkable mentor of how to keep the questions of learning and teaching alive into your later years. I'm deeply appreciative of people who have, throughout their life, held on to those questions of learning and teaching and keep asking them; and to all the staff who work behind the scenes to make programs work for the students. They are too many to name, but they know who they are!

.